Outsized Ambitions: Connecticut’s Bold Claims

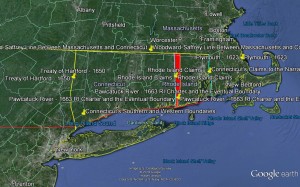

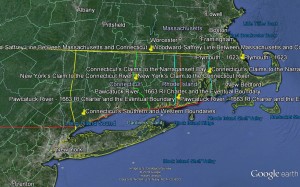

Although English colonists first settled in Connecticut in the 1630s, Connecticut lacked a charter until 1662. The borders established in that charter overlapped with the claims of a number of surrounding colonies. Though the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the plucky Puritan colony found itself embroiled in border disputes with New York, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. Connecticut even claimed lands in present-day Ohio. The text of Connecticut’s charter set the stage for future claims by the colony, decades of disputes, and the ultimate settlement of its current boundaries.

The land grants in Connecticut’s 1662 Charter were broad and ambiguous. King Charles II issued the following definition of the colony’s borders:

“all that Part of Our Dominions in New-England in America, bounded on the East by Narraganset-River, commonly called Narraganset-Bay, where the said River falleth into the Sea; and on the North by the Line of the If Massachusetts-Plantation; and on the South by the Sea; and in Longitude as the Line of the Massachusetts-Colony, running from East to West, That is to say, From the said Narraganset-Bay on the East, to the South Sea on the West Part, with the Islands thereunto adjoining.”[1]

The Dispute with Rhode Island

Consequently, settlers in the newly-chartered colony of Connecticut seized upon the ambiguities in this charter to make the largest claims possible. This was especially true of its claims in present-day Rhode Island. Connecticut, like Massachusetts, effectively denied the existence of the tiny Rhode Island settlement and attempted to claim rights to lands all the way to the Narragansett Bay, on the eastern side of present-day Rhode Island. However, in 1663, Rhode Island received a charter of its own from King Charles II, which placed the Connecticut border further west at the Pawcatuck River:

“[T]o the Governour and Company of Connecticutt Colony, in America, to the contrary thereof in any wise notwithstanding; the aforesavd Pawcatuck river haven byn yielded, after much debate, for the fixed and certain bounces betweene these our sayd Colonies, by the agents thereof; w hoe have alsoe agreed, that the sayd Pawcatuck river shall bee alsoe called alias Norrogansett or Narrogansett river; and to prevent future disputes, that otherwise might arise thereby, forever hereafter shall bee construed, deemed and taken to bee the Narragansett river in our late Irrupt to Connecticutt colony mentioned as the easterly bounds of that Colony.”[2]

Despite the fact that Connecticut’s agent in London for negotiating its charter, Governor John Winthrop, had agreed to the boundary in the Rhode Island charter, Connecticut settlers still attempted to claim lands further east. Connecticut’s participation in King Philip’s War in 1676 enabled to colonists to claim that they owned the lands by conquest. Reciprocally, Rhode Island asserted rights to lands further into Connecticut up to the Mystic River. The Crown attempted to resolve the issue by carving out a new colony, known as King’s Province, from the disputed lands in 1665. Neither Connecticut nor Rhode Island claimants accepted King’s Province and the Crown did not attempt to enforce its existence.[3]

After a number of rounds of arbitration by different royal commissioners, Connecticut accepted the Pawcatuck River boundary in 1702. Yet Rhode Island rejected this agreement, and Connecticut then renewed its claims to the Narragansett Bay. The English Board of Trade appeared to prefer Rhode Island’s claim in a 1723 ruling, but the board wanted to seize on the discord to join the colonies and exert closer Crown control over them, as had been planned in the ill-fated 1685 Dominion of New England. Sensing their shared interest in continued independence, the two colonies then agreed in 1727-1728 to survey a line that followed the Pawcatuck River up to the end of a tributary called the Ashaway River. The line ran from that point north to another point twenty miles west of Warwick Neck in the Narragansett Bay, and then up to the Massachusetts line. This line was re-drawn as it now stands in 1840.[4]

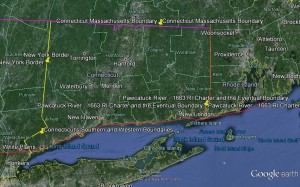

The Northern Boundary

The 1662 Connecticut Charter specified that the colony’s northern border would be the southern boundary of Massachusetts. The 1629 Massachusetts Charter placed the line:

“within the Space of three English Myles on the South Parte of the said Charles River, or of any, or everie Parte thereof; and also, all and singuler the Landes and Hereditaments whatsoever, lyeing and being within the Space of three English Myles to the Southward of the Southermost Parte of the saide Bay called Massachusetts, alias Mattachusetts, alias Massatusets Bay.”[5]

Two inexperienced surveyors, Nathaniel Woodward and Solomon Saffery, fixed the line by marking a point three miles south of what they thought was the end of the Charles River. They then sailed around Cape Cod, down the coast, and up the Connecticut River to Windsor, where they marked another point. The line they established, known as the Woodward-Saffery line, was unclear and appeared to place several northern Connecticut towns within Massachusetts limits. After numerous surveys, the colonies eventually fixed the line around its present-day location in 1714, though there continued to be minor disputes up to 1826.[6]

The New York Line

The Connecticut Charter of 1662 claimed lands west to the South Seas, which are now considered the Pacific Ocean. At the time of the charter, the Dutch controlled present-day New York, but the English Crown did not refer to Dutch claims in its charter to Connecticut. In 1650, Connecticut had negotiated the Treaty of Hartford with the Dutch Governor Peter Stuyvesant, which fixed the New York-Connecticut boundary ten miles east of the Hudson River. The Dutch government never officially accepted the treaty. When the English took over control of Dutch lands in 1674, the new colony of New York claimed lands all the way to the Connecticut River. In 1684, Connecticut and New York resolved the dispute by having surveyors draw a line twenty miles east of the Hudson. Connecticut received a panhandle so that it could keep its towns of Stamford and Greenwich. New York gained a small strip of land cutting north and slightly east into Connecticut, which was known as “the Oblong.”[7]

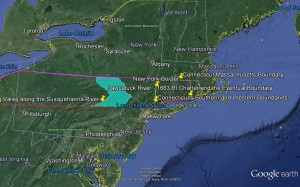

Western Claims

As Connecticut’s population grew in the 1750s, some residents of Connecticut decided to push the claims of the 1662 charter and establish western towns beyond New York. Connecticut citizens settled in the Wyoming Valley near the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, and some colonists formed the Susquehanna Company to pursue those claims. Others formed the Delaware Company with the goal of settling along the Delaware River. After contentious internal debates, Connecticut’s government in Hartford officially annexed this land, calling it Westmoreland County. After years of sometimes bloody fighting between Connecticut and Pennsylvania colonists, Connecticut surrendered its claims in 1786 in exchange for Pennsylvania’s promise to help Connecticut receive a land concession further west, which would become known as the Western Reserve.

At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Connecticut successfully defended its claim to the Western Reserve in present-day Ohio. Other states, like Pennsylvania, held similar claims and shared an interest in establishing the Connecticut precedent. Connecticut may also have cut a deal with some southern states over the slavery issue to receive votes in support of its claim. Connecticut quickly sold the lands in the Western Reserve to speculators in 1795 and used the proceeds to fund public education.[viii]

Conclusion

The Google Earth map available through the link at the top of this page shows the evolution of Connecticut’s borders and claims up to their present form. Borders in the colonial period were highly fluid. The time slider shows how they evolved. Negotiating borders involved the actions of the Crown, officials like the Board of Trade, colonial governments, and local settlers. The interests of these different groups often collided. Charters became critical evidence for pursuing claims, both before Crown arbiters and between colonies. Yet aggressive settlers’ willingness to ignore charters meant that borders often did not reflect the original grants. Antagonistic relations between the colonies over borders persisted through the early period of American independence. Compromises resulted in some of the anomalies in Connecticut’s shape, including its panhandle and northern “notch.” Ultimately, Connecticut’s charter did not set borders, but rather initiated a debate over space and sovereignty that took nearly one-hundred and fifty years to conclude.

Notes:

[1] “Charter of Connecticut – 1662.” Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, The Avalon Project. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ct03.asp. Accessed April 20, 2014.

[2] “Charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations – July 15, 1663.” Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, The Avalon Project. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ri04.asp. Accessed April 30, 2014.

[3] Alexander Johnson, Connecticut: A Study of a Commonwealth-Democracy (New York: Houghton Mifflin 1896), 209-214.; C.W. Bowen, The Boundary Disputes of Connecticut (Boston: J.R. Osgood and Company, 1882), 32, 40-45. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015027757692. Accessed April 21, 2014.

[4] Johnson, 213-214.

[5] “The Charter of Massachusetts Bay: 1629.” Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, The Avalon Project. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass03.asp. Accessed April 20, 2014.

[6] Johnson, 207-208; Bowen, 19-20; Henry Wolcott Buck, “Connecticut Boundary Line Surveys.” 1938, pp. 209-213. https://www.csce.org/images/1938-ConnecticutBoundarySurvey1of2.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2014.

[7] Mark Stein. How the States Got Their Shapes (New York: Harper Collins, 2008), 47-48, 198-199.; Johnson, 205-207.

[8] Robert A. Wheeler, “The Connecticut Genesis of the Western Reserve, 1630-1796,” Ohio History 114 (2007), pp. 57-78. Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ohh/summary/v114/114.wheeler.htmlA. Accessed April 20, 2014.