Max Moisel, born in 1869, joined the Berlin publishing company of Dietrich Reimer in 1888. With the help of Moisel and other talented cartographers such as Paul Sprigade, Reimer rose to the forefront of German efforts to map their colonial possessions in the late nineteenth century. In 1897, the publishing company worked to expand its workforce with the understanding that the Imperial German government, still without a colonial cartography bureau, would, according to Rudolf Hafeneder, “guarantee permanent work assignments on a regular basis.” Two years later, in 1899, Dietrich Reimer became the quasi-official cartography department for the German government, with the agreement that all official material received from protectorates would be processed through an institution at Reimer. During this period, Moisel rose to prominence as a cartographer specializing in the African continent, eventually helping to draft maps that assisted the Allied partition of German colonies following WWI.

Depicting German East Africa

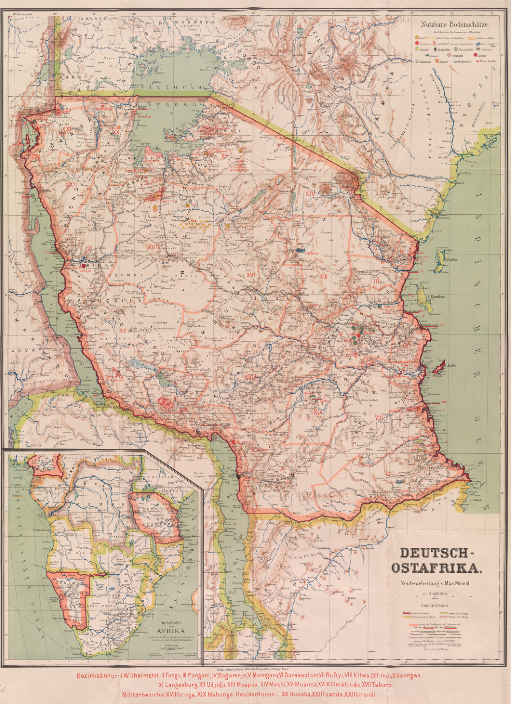

Moisel’s map of German East Africa, published in 1910, depicts the colony in great detail, with a scale of 1:2000000. First established under the German East Africa Company in 1885, German East Africa became an official protectorate of Imperial Germany in 1890. This map represents one of the last maps published of the area while it remained in the hands of the Germans, who would lose all colonial possessions following their defeat in WWI.

The details included by Moisel in this map represent a larger German colonial mindset. Firstly, the map includes an inset that depicts the southern half of Africa, including all three major German colonies- Kamerun, German South-West Africa, and German East Africa- while leaving out the small West African colony of Togoland. Shown in this insert are major sea routes between possessions as well as railroads and major roads within the colonies themselves. Secondly, the main map itself goes to great lengths to mark the location of natural resources within German East Africa. Together, these inclusions help to highlight the economic mindset with which the Germans approached colonial ventures. Germany, a young nation located in Central Europe and wedged between France and Russia, two traditional powerhouses, looked to its colonies to provide economic independence. While the outcome of WWI cut Germany’s colonial ventures short, Moisel’s map remains as a reminder of this larger mindset.

Colonial Tensions

Imperial Germany was not the only country that recognized the vast resource potential that lay in Southeast Africa. One contemporary report issued by the Royal Botanical Gardens in 1896 recognized German East Africa as the most valuable German possession in Africa, but also the most underdeveloped. Additionally, the German procurement of East Africa temporarily blocked the project put forward by Cecil Rhodes to build a transcontinental British railway running from the Cape Colony in the south to Cairo in the north. Tensions only grew between the two countries after the start of a German naval building plan in 1890, formulated with the goal of challenging British naval superiority. The development of a German blue water navy simultaneously undermined British security at home and abroad while strengthening German overseas claims. This led to a souring of Anglo-German relationships and was one contribution to the series of alliances that allowed for the First World War.

Tensions over the former East African colony existed between Germany and the British Empire even after German colonies were confiscated by the Allied powers following WWI. One British publication from 1939 epitomizes this tension, going to great lengths to disprove any German rights to its former African colonies, suggesting they were gained from natives through trickery and deceit. Ultimately, German leadership chose to forgo claims on the African continent in order to pursue a landed empire in Eastern Europe. However, this map of German East Africa remains as a reminder of German colonial ambition at the turn of the 20th century.

Sources

“German Colonies in Tropical Africa and the Pacific.” Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew) 1896.117/118 (1896): 174-185. JSTOR. Web.

Hafeneder, Rudolf. “German Colonial Cartography: 1884-1919.” PhD. Diss., Bundeswehr University Munich, 2008. Print.

Lyne, R.N. “Germany’s Claim to Colonies: The African Mandates.” Journal of the Royal African Society 38.151 (1939): 273-280. JSTOR. Web.

Pierard, Richard V. “The German Colonial Society.” In Germans in the Tropics. Ed. Arthur J. Knoll and Lewis H. Gann. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1987. Print.

Schnee, A. Deutsches kolonial-lexikon. Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1920. Print.

Turk, Eleanor L. The History of Germany. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1999. Print.

Zimmermann, E. The German empire of Central Africa as the basis of a new German world-policy. New York: George H. Doran Company, 1918. Print.