The First Map of the New World

The First Map of the New World

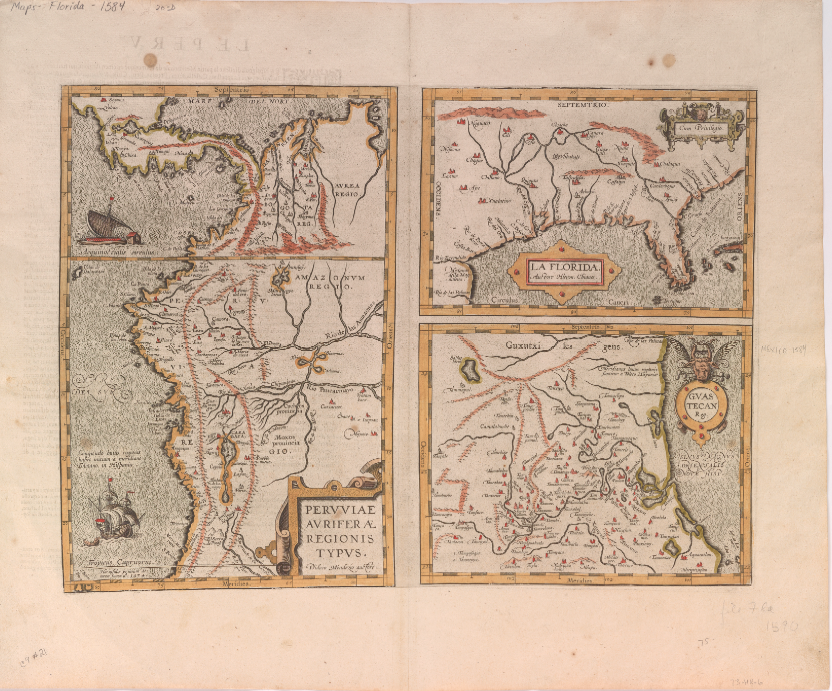

The world changed in 1492 when Christopher Columbus set foot in the Bahamas and claimed the New World for the Crown of Castille, modern day Spain. While maps depicting this New World were likely created prior to 1584, Abraham Ortelius’ Peruviae Auriferae Regionis Typus is one of the first widely published maps of the area. The map shows three different regions of South America claimed by Spain: Peru, Florida, and Guastecan.

Compiling a 16th Century Atlas

Ortelius’ map was produced for the third edition of the atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, which is considered to be the first modern atlas. At the time, there was public demand from well-educated elites for an image of Spain’s new territories that had arisen from the growing imperial emphasis on discovering and colonizing the New World. Ortelius did his best to provide this, but had little information available, as he had never been to South America. The locations of different Indian settlements are documented, but little else. Ortelius cannot be credited for creating any of these maps. As a result of engravings, the maps of others were available for Ortelius to borrow for his own atlas. The map of Peru is attributed to Didaco Mendezio, about whom little is known, while the image of Florida is attributed to Jeronimo de Chaves who had copied an earlier manuscript map by Alonso de Santa Cruz. The creator of the Guastecan map is unknown. Ortelius pulled these maps together onto one page and contributed descriptions of each map on the back of the page. By using letters and travelogues from explorers such as Ponce de Leon, Cabeza de Vaca, and Vazquez de Allyon, Ortelius attempted to create a better understanding of the spaces. This map was one of seven of the New World added in 1584 to the Theatrum. By comparison, the rest of the world was given a staggering 105 maps. The contrast illustrates what little information the public had on early exploration of the Americas.

Perceptions of the New World

The Latin text on the back of the page can offer modern scholars an insight into the minds of their sixteenth century counterparts. Ortelius wrote about the climate in Peru, comparing it to Spain. He excitedly told of all the gold that had been found in the area. His description of Florida was particularly colorful as he described the natives as barbarians who ate spiders, serpents, and all sorts of venomous creatures. Ortelius explained away these texts as filler for what would have otherwise been blank spaces.

Ortelius uses ships to further convey the Spanish claim to the region, and several galleons with Spanish flags are depicted off the coast of Peru. His use of color helps emphasize the coastlines, mountains, and other elements represented. Art, cartography, and scholarship combine to make an aesthetically pleasing and informative map. His map pulls from different disciplines in an attempt to educate a curious society. Exploration of the New World continued to excite people in the sixteenth century as colonization grew and more territory was discovered. Peoples’ perceptions and understanding of the world were changing and Ortelius’ maps helped to shape early ideas and images of the New World.

Sources

van den Broecke, Marcel. “The Significance of Language: The Texts on the Verso of the Maps, in Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum.” Imago Mundi 6 (2008): 202-210. Web.

Cline, Howard F. “The Ortelius Maps of New Spain, 1529, and Related Contemporary Materials, 1560-1610.” Imago Mundi 16 (1962): 98-115. JSTOR. Web.

Nuti, Lucia. “The World Map as an Emblem: Abraham Ortelius and the Stoic Contemplation.” Imago Mundi 55, (2003): 38-55. JSTOR. Web.

Reinhartz, Dennis. “The Americas Revealed in the Theatrum.” In Abraham Ortelius and the First Atlas: Essays commemorating the Quadricentennial of his Death. Utrecht: HES Publishers, 1998. Print.

Unger, Richard W. Ships on Maps: Pictures of Power in Renaissance Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. Print.